Broadband Terms, Questions, and Myths

This is a working document developed in partnership with the City of Chicago in an effort to demystify broadband and work towards a more connected Chicago. It was informed by input from community-based organizations, including McKinley Park Development Council, Neighborhood Network Alliance, Resurrection Project, and South Shore Works.

This document is presented in three sections: basic terms, frequently asked questions, and finally a few myths.

Terms and Definitions

Broadband: Broadband is, in short, fast Internet. We’ll get into the details below, but “fast” usually means that the connection is sufficient to send and receive multiple video streams at the same time. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) currently defines broadband as Internet with a download speed (or bandwidth) of at least 25 Mbps and an upload speed of at least 3 Mbps.

Bandwidth or Speed: These are technically slightly different, but both measure how much data can be transmitted by an Internet connection.

Megabits per Second (Mbps): Megabits per second, or Mbps, is the unit in which Internet speed is typically measured. 1 Mbps is approximately what it takes to watch a standard-definition video on YouTube. Larger numbers of Mbps allow you to send or receive more data per second.

Downstream or Download: Downstream refers to data that you download from a site, like streaming a TV show. For example, 25 Mbps download speed refers to the speed at which you can download data from a site.

Upstream or Upload: Upstream refers to data that you send, like a video of yourself in a video conference, an email, or an upload of a photo to social media. For example, 3 Mbps upload speed refers to the speed at which you can upload data to a site.

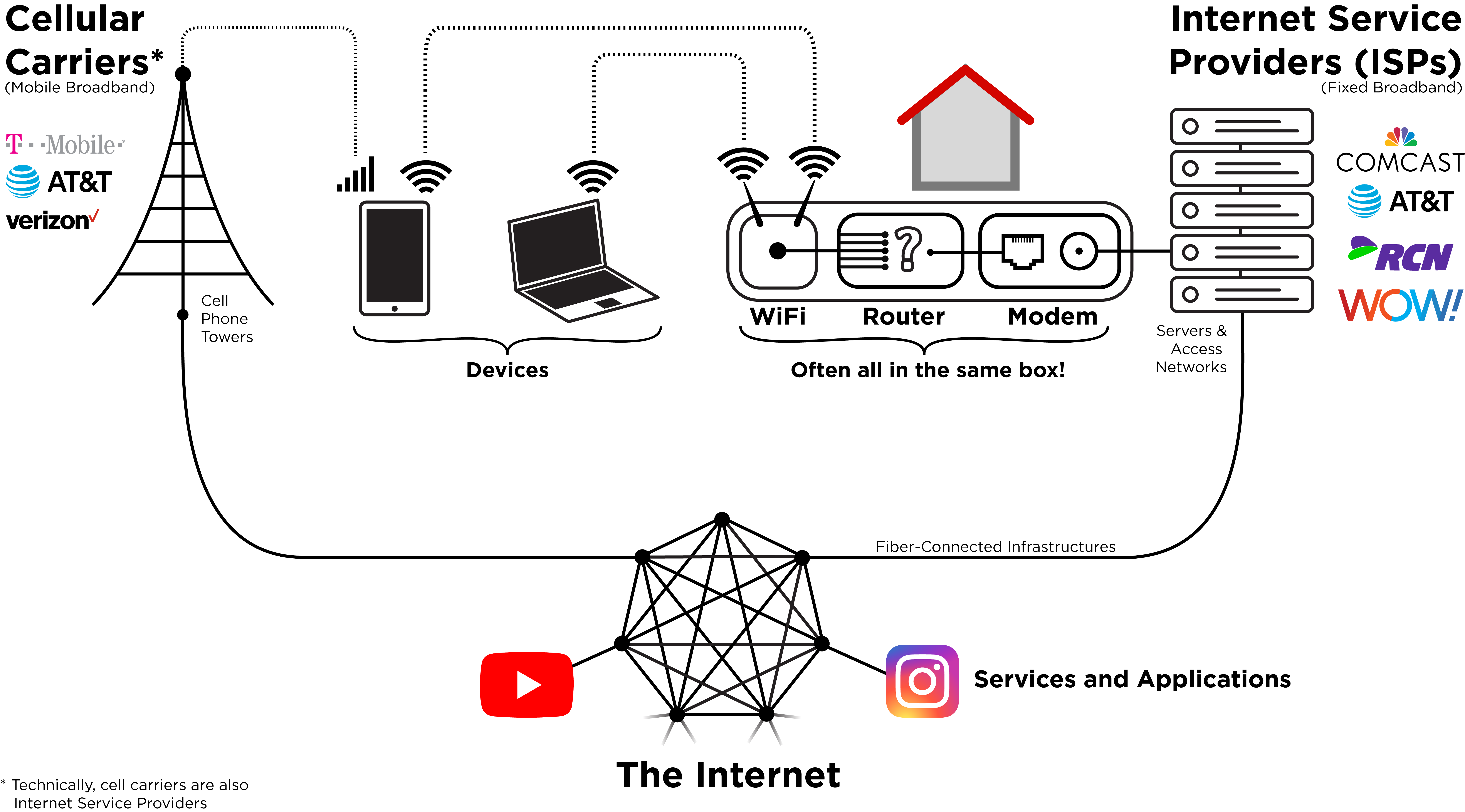

Mobile Broadband: Mobile Broadband is the Internet you access through a smartphone. This connection is provided through cellular companies like AT&T, Verizon, or Sprint.

Fixed Broadband: Fixed Broadband is the Internet that enters your home on a cable, also known as at-home broadband. This connection may be provided by Internet Service Providers like Comcast, AT&T, RCN, or WOW.

Internet Service Providers (ISPs): Internet Service Providers, or ISPs, are companies that provide Internet service to individual consumers and businesses. In practice, this usually refers to fixed broadband, although mobile phone companies can also provide Internet access. Companies like Comcast, AT&T, RCN, and WOW are examples of ISPs that serve Chicago.

Cellular Carriers: Cellular carriers are companies that build and provide cell phone infrastructure (for example, cell towers) and services (such as a cell-phone plan). Today, cellular carriers may also be ISPs, although an ISP typically refers to a fixed broadband ISP. Cell carriers include companies like Verizon, Sprint, and AT&T.

Device: A device is a piece of electronic equipment that can connect to the Internet. This includes both traditional devices like computers, smartphones, and tablets, as well as security cameras, “smart” appliances like refrigerators or thermostats, and printers or home entertainment systems like gaming consoles, Google Chromecasts, or Amazon Fire TV. Devices can connect over wires or wirelessly.

Ethernet:

Ethernet is the standard form of short-distance in-home Internet cable. You can plug a computer or laptop into an Ethernet cable to connect to the Internet. Ethernet plugs (and sockets) look like old phone plugs (and sockets), except they are wider:

![]()

Modem: A modem converts the Internet signal from your ISP into a form that your devices can connect to. Specifically, it translates signals from a transmission cable like “coaxial cable” (originally used as the cable to bring TV into the home), into the digital signals used for your Ethernet connections or Wi-Fi.

Router: A router directs incoming data to the appropriate device. It may have Ethernet plugs or “ports,” which appliances such as computers or video game consoles can connect to.

Wi-Fi:

Wi-Fi broadcasts Internet signals over the air over short distances (e.g., within a home, office, or coffee shop). You’re probably familiar with its symbol:

![]()

Note that in many homes, the modem, router, and Wi-Fi are all contained in a single physical box. The ISP may rent these to you (usually as one box), or you can purchase them. Your setup may vary, but to connect to your network wirelessly, you need all three elements in some form.

Coaxial Cable: Coaxial cable (or “coax”) is a metal cable, perhaps most familiar as the cable that delivers the signal to your television. Data is transmitted as electrical voltage.

Fiber: Fiber, in the context of the Internet, is a type of cable made out of glass or plastic that allows data to be transmitted as light instead of as an electrical voltage. Fiber can usually carry much more data than older infrastructures with coaxial cables. While long-distance links between cities are generally fiber, we often speak of “fiber” Internet when the fiber reaches all the way to consumers’ residences.

This diagram illustrates how the components listed above work together to bring Internet to users. (Click to expand.)

Frequently Asked Questions

- What is broadband Internet?

- What is the difference between fixed broadband and mobile internet? Why are they not the same?

- How does one connect to the internet? How does it actually work?

- Does my internet speed change if I am plugged directly into the modem compared to getting service over Wi-Fi?

- Why does my internet speed seem to be the same, even though I paid extra for more speed?

- How can I test my Internet speed?

- Why do only certain Internet Service Providers service my neighborhood?

- Why does my neighbor get faster internet even though we have the same ISP and modem?

- Where are the City of Chicago open or free Wi-Fi spots in or near my community?

- What is the potential that an Internet connection can bring you as an individual or a small business?

- Should I be nervous about online surveillance or other Internet privacy issues?

Basics

Informally, broadband Internet is just fast Internet. This is defined in terms of the amount of data you can transmit per second. Currently, a broadband connection is one with a “bandwidth” of at least 25 Mbps for downloads and 3 Mbps for upload. The unit, Mbps or “megabits per second” sounds like a lot, but we can convert it into familiar units.

A megabit is just one eighth of a megabyte, and a gigabit (1000 megabits) is one eighth of a gigabyte. That means that with a 25 Mbps connection, you can download 1 Gigabyte of data in 5.3 minutes (or 0.1875 Gigabytes in one minute). For comparison, a typical video conference uses about 1-1.5 Mbps in each direction, and a normal Netflix video also uses about 1 Mbps. The Federal Communications Commission offers a table of how much bandwidth they think various activities require.

What is the difference between fixed broadband and mobile internet? Why are they not the same?

Mobile broadband is delivered by a mobile provider to your phone on radio waves. In the City of Chicago, it is generally available anywhere with cell phone service. By contrast, fixed broadband enters your house on a cable: coaxial (as for cable TV), “fiber,” or in very old cases, telephone lines.1 In high-density places like the Loop, mobile and fixed broadband speeds can be comparable, but in most places fixed broadband is faster and more reliable: with fixed broadband, you are paying for speed and reliability in a specific place. The overall difference in speeds is also narrowing with 5G (5th Generation) mobile, with speeds that can exceed 1 Gbps (1000 Mbps). However, phones capable of achieving those speeds are currently quite expensive.

In addition to the method of delivery (radio versus cable) and speed of data, another distinction is how much data costs. Comcast Xfinity offers 1200 gigabytes of data per month with basically any of its fixed broadband plans, whereas AT&T caps monthly data on mobile plans at 30 GB and Verizon imposes caps at around 15 GB (though you can always pay more).

Ultimately, however, both mobile and fixed broadband connect to the same Internet.

How does one connect to the internet? How does it actually work?

The Internet is a physical infrastructure of fiber, cables, and servers, connecting the entire planet. The Internet hosts the world wide web and other services like email and teleconferencing. To connect to the Internet, you need an Internet-enabled device like a smartphone or a computer, and an Internet connection. Today, that connection is usually provided to consumers in one of two ways: through mobile or through fixed broadband (as discussed above). Individuals buy phone plans and home internet service through mobile carriers or Internet Service Providers. However, Wi-Fi – fixed broadband internet broadcasted over the air, with limited distance – is also available in many public places from cafes to libraries.

This depends on the quality of your Wi-Fi access point, how it is set up, and where it is placed.

Most ISPs rent hardware (the modem/router/Wi-Fi) that is designed to match or exceed the broadband contract that you buy. If you have your own hardware, it may not be adequate to transmit the speeds that you get on your modem.

More broadly though, the answer is likely yes. You tend to lose bandwidth from interference or just being far from your Wi-Fi. Normal Ethernet cables can run about 100 yards. If you work in your bedroom and the Wi-Fi is in the kitchen, if it’s easy to run the wire, it can help. Wi-Fi extenders can help too, though they usually require careful configuration to work well.

We suggest plugging directly into your router and testing your speed with speedtest.net. (See “How can I test my Internet speed?” below for instructions.) If your speed is much higher when on that wired connection, it may be worth moving your Wi-Fi or running the wire.

Why does my internet speed seem to be the same, even though I paid extra for more speed?

If your Wi-Fi is the limiting factor in your connection, you will not see a speed boost with a more expensive contract. Most ISPs offer tools for checking that you are getting the Internet performance you’re paying for (att.com/support/speedtest or speedtest.xfinity.com). You can also go to sites like speedtest.net, to see if your bandwidth lines up with your contract.

One way to get a better handle on the speed your ISP is delivering is to plug a laptop directly into the cable modem with an Ethernet cable, and then run the speedtest with that “wired” connection. This should be close to your purchased speed. If you are seeing slower speeds over the Wi-Fi – on other devices or in other areas of your house, then the Wi-Fi itself is likely the “bottleneck” – the limiting factor in your setup. In other words, the ISP may be delivering data to your home faster than the Wi-Fi can send it to your computer, smartphone, or tablet!

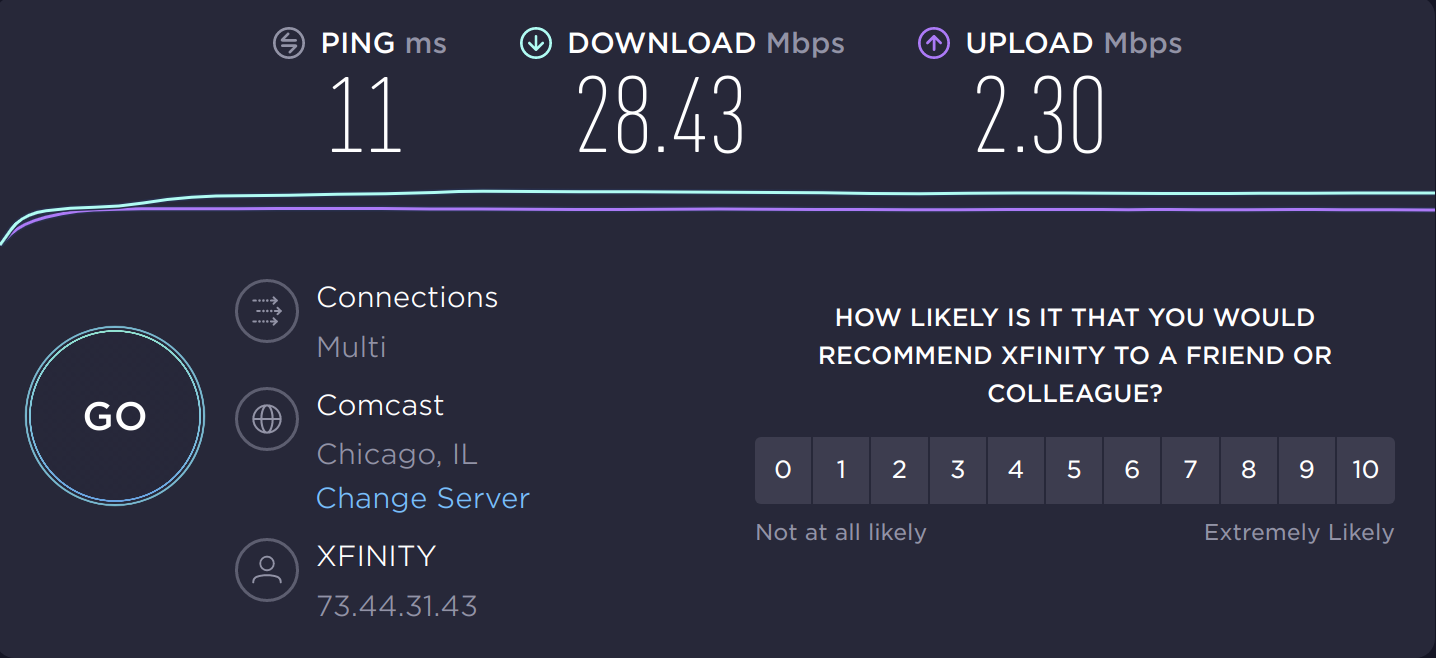

How can I test my Internet speed?

To test your Internet speed, you can visit speedtest.net and then click “Go.” When the test completes, you’ll see something like this:

The “Download” speed in Mbps is what people usually think of as their speed. It is used for streaming video or downloading files. The upload speed, which is usually much lower, measures how much you can send per second. As noted above 25 Mbps download speed and 3 Mbps upload speed defines a broadband connection, according to federal standards. As you can see, this connection has an upload speed that does not qualify as broadband.

Connectivity in Chicago

Why do only certain Internet Service Providers service my neighborhood?

Internet infrastructure, like fiber and coaxial cable, is owned by the companies that have installed it, and it is expensive to install. In each neighborhood, private companies make choices about what to build. Those choices reflect market forces and a series of local histories. For example, companies may have believed that the costs to dig a ditch for fiber exceeded the profits that they would recuperate by selling contracts. That will depend on the density of people, the likelihood of uptake, and the costs of digging the ditch.

The limited number of providers per neighborhood also reflects the larger history of American investment in the Internet. The Internet was initially developed with taxpayer money by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and the National Science Foundation (NSF) in the 1970s and 1980s. However, it was privatized in 1994-1996. Since then, private companies have paid for much of the physical infrastructure investment, for both local delivery and long-distance connections. Other countries have followed other paths, with the government building large parts of the Internet backbone and leasing that resource back to private ISPs.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) lists prices for Internet contracts across countries. While their table is not a perfect comparison (the contracts are different in each country), it’s telling that the US is among the most expensive countries for broadband Internet in the OECD.2

Why does my neighbor get faster internet even though we have the same ISP and modem?

There are a lot of factors that affect Internet speed. If the modem and ISP are the same, some factors that may influence the speed of your Internet might be:

- Bandwidth: Your Internet speed may differ from your neighbor’s based on your contract with your ISP and the speed you pay for. In short, your neighbor might have a more expensive contract than you. Internet connection speeds with bandwidths greater than 25 Mbps in the downstream direction and 3 Mbps upstream are classified as “broadband,” but in much of Chicago, speeds as high as 1000 Mbps are available downstream.

- Wi-Fi: In many cases, the modem is the same box of electronics as the router and the Wi-Fi access point. However, these three different functions can be separated. The modem converts the coaxial cable into an Ethernet cable, the router makes it possible to identify devices (smartphones, computers, smart speakers, etc.) on your home network, and the Wi-Fi access point broadcasts signals over the air. The question suggests that the modem is the same, but the router and Wi-Fi may be different! So your neighbor may have a fancier Wi-Fi device, that is performing better.

- Wi-Fi placement: If you and your neighbor are both using the same box (modem, router, and Wi-Fi) from your Internet Service Provider, and you’ve connected it the same way, the Wi-Fi could still be the issue. The placement of the Wi-Fi matters a lot. Some tips:

- It helps to place your Wi-Fi box far from large metal objects. Appliances like stoves or microwaves can block the signal, so that you can’t use the bandwidth you pay for.

- It can also help to put the Wi-Fi high up – on a bookshelf, for instance – since most furniture in an apartment or house is on the floor. Simply getting it higher puts less “stuff” between you and your Wi-Fi.

- Infrastructure: It is also possible that the infrastructure the ISPs have installed is not exactly equal. We’re working to measure whether or not the Internet performs equitably across the entire city. In this work, we will account for the features above. For example, we know that people use different contracts, and we’ll work to take Wi-Fi out of the equation. But accounting for those factors, do the ISPs deliver the same quality of infrastructure in the Gold Coast and the West Side?

- Temporary Conditions: Unlike the traditional phone network, the Internet was designed as a shared resource: everyone uses the Internet at the same time. This is why you never get a busy signal when you try to load a web page or use any Internet application, like YouTube or Facebook. The flip side of this is that if many people are using the Internet at once, the applications do slow down. Internet protocols were designed so that everyone gets their fair share of bandwidth, but such sharing occurs on average, not over short time windows, and some applications take more than their fair share regardless.

It’s also important to collect good data on Internet performance! If you think that your neighbor is getting better service, we recommend using speedtest.net to measure your speed. Speedtest tests how much data you can send and receive per second, and it allows you to make meaningful comparisons.

Where are the City of Chicago open or free Wi-Fi spots in or near my community?

The City’s libraries all provide free Wi-Fi. You can find a map of libraries here. Places in the city where internet and computer access, digital skills training, and online learning resources are available can be found here, though that resource may be a bit dated. During the COVID pandemic, Xfinity has made Wi-Fi access points in commercial locations available to the public. You can find a map of these Wi-Fi access points here. Comcast has also made ten lift zones – safe spaces with free Internet for students and families. If you have a child in Chicago Public Schools, you may also be eligible for free (yes, actually free!) Internet through the Chicago Connected program.

Digital Literacy

Simply put, today’s world is mediated through the Internet. People communicate through email, social media, and teleconferencing, order goods and services, track and develop their finances, seek entertainment and enlightenment, all over the Internet.

A 2019 survey by the National Telecommunications and Information Administration found that at least half of American adults use the Internet for: email (90%), text and instant messaging (90%), social media (74%), voice and video calls (51%), watching videos (74%), streaming music, radios, and podcasts (56%), using financial services (70%), shopping and consumer services (72%). These numbers continue to increase, particularly in the context of the coronavirus pandemic.

From the small business side, more than 10% of American adults have sold goods on the Internet and 7.5% have sold services on the Internet.

Privacy and Security Online

Should I be nervous about online surveillance or other Internet privacy issues?

There are two distinct areas of concern with privacy online. The first is information that you share and the second is information that you did not intend to share.

You should never provide your personal data – name, billing information, etc. – to unknown websites online or over email. In general, you should avoid putting highly-sensitive private information like your social security number into email. Parents know that what goes online can never be taken back. So you should be aware and thoughtful of what you want to share, and with whom. Of course, one of the joys of the Internet is being able to share photos or experiences with friends and family. This is safe. Just be aware of who can see that content.

The second area of concern is surveillance and stolen or intercepted information.

Because Internet Service Providers sit in between your home and the rest of the Internet, they can see some of your traffic – what you do online – as it enters and leaves your home. The ISP has to see some information – like the intended destination server – in order to request and retrieve content for you.

However, the information that they can see is more limited than you might think. In the past, most Internet traffic was unencrypted. That means that anyone who transmitted data could read its contents. The ISP thus had a very good view into all activities on the Internet, including details such as web pages you might be visiting. Today, however, most Internet traffic is encrypted. Encryption makes it virtually impossible for even the ISP, that is delivering your data, to read its contents! However, just as a letter is private but needs a public address on the envelope to be delivered, the destinations of your traffic can be seen by the ISP. A few technical services are also still unencrypted.3

For the bigger picture: Cellular carriers and online services (e.g., Google, Facebook) have a far more extensive history and practice of collecting data and tracking for advertising than traditional, fixed broadband ISPs. For example, Google records all of the searches that you send to them, associates those searches with your account, and potentially records all of the locations that you visit with your phone as well (you can control this, in your privacy settings). On the other hand, while traditional ISPs do have the ability to watch some traffic, they tend to do less of this. They tend to monitor traffic to ensure security (e.g., detecting infected devices) and for services like parental controls.

Common Myths and Misconceptions

- Similar to cell phone companies, I can shop around for the best internet price and choose any internet company that I want (RCN, Comcast, AT&T, etc.) to be my service provider.

- If I have a weak Wi-Fi signal in my apartment, is it because my internet service provider is not providing the internet speeds that my contract dictates?

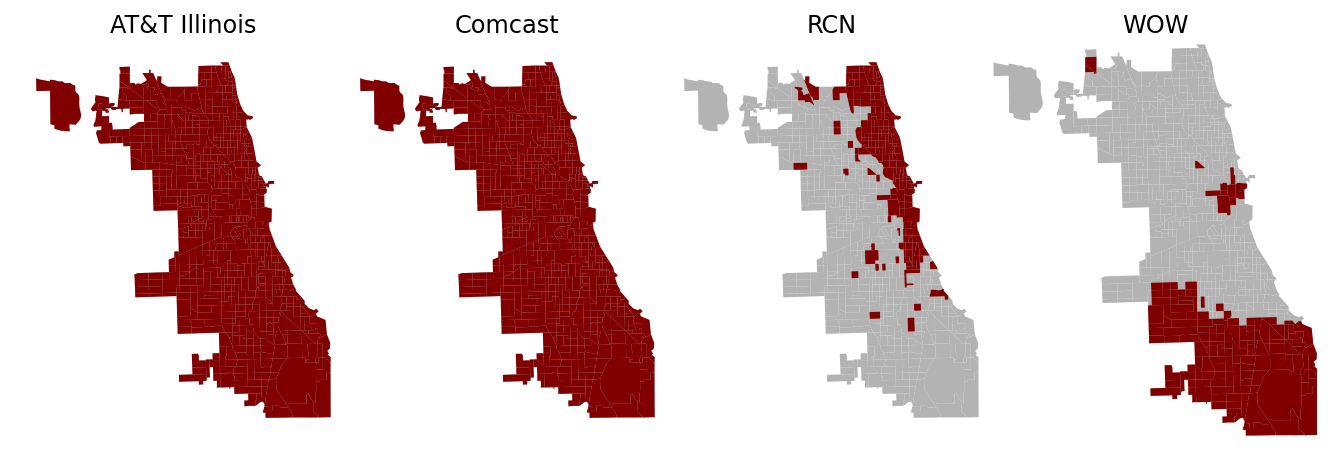

Unfortunately, the coverage of Internet Service Providers is much more geographically constrained than cell phone carriers. The coverage maps for four of the biggest ISPs in Chicago – Comcast, AT&T, RCN, and WOW – are shown below, based on data from the Federal Communication Commission (FCC).

The FCC data are known to sometimes report services as available in places where they are not. Still, it is clear that RCN and WOW do not serve the entire city.

In addition, the speeds available from different ISPs may also differ, and single ISPs may offer different speeds in different neighborhoods, depending on the infrastructures that they have installed.

ISPs generally lease equipment with their broadband services that are matched to outperform the contracted bandwidth. If you own your own equipment, that could be the issue, as it might be providing a Wi-Fi signal that is too weak. But even if you rent from the ISP, you may be able to improve your Wi-Fi signal through very simple steps, such as moving the Wi-Fi away from big metal objects, putting it up high, like on a bookshelf, or simply moving closer to the Wi-Fi access point. Wi-Fi is known to not travel as well through stone, brick, and other materials common in Chicago housing as compared to traveling through the open air, or even materials like wood.

Notes.

-

Satellite is a bit of a special case, that we’ll leave to the side. ↩

-

Only Norway is higher in fixed USD, and only Mexico is higher at Purchasing Power Parity. ↩

-

The Domain Name System (DNS) that maps Internet names (google.com) to computer-readable addresses, for instance, is unencrypted. In short you ask DNS, “where is Google” and DNS responds “216.58.192.174.” This means that the DNS server, or anyone who sees your request, can know that you asked about Google. Until a few years ago, your ISP typically operated your DNS, making it possible for them to see this traffic. Most users still use their ISP’s DNS service by default. Recent developments have begun to encrypt the DNS and give users the option to send their DNS traffic to other providers (e.g., Google). That doesn’t necessarily solve the privacy problem, but simply moves it to another provider. Some solutions have been proposed to improve the privacy of DNS, for instance creating “clearinghouses” for DNS requests. For example, a second party (e.g., an ISP) can forward encrypted DNS requests to a server, so that the server does not learn who originally made those requests and the ISP does not know the content. Some other services, like Server Name Identification (SNI) are also unencrypted. ↩